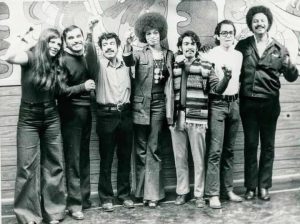

I have a photograph from April 1973.

Boulder, Colorado. The Crusade for Justice. In the frame stand Rodolfo Gonzales — Corky — founder of the Crusade. Beside him, Angela Davis, scholar and radical voice of a generation. And on the far right, a young Jesse Jackson.

Three leaders. Two movements. One moment.

Three leaders. Two movements. One moment.

That gathering symbolized something that is often forgotten today: solidarity between the Black and Chicano civil rights movements during a time of intense activism — and intense federal scrutiny. These were not safe years. Organizations were infiltrated. Leaders were surveilled. Movements were fragmented from within and attacked from without.

And yet they stood together.

When I heard that Jesse Jackson had died at 84, I didn’t think first about presidential campaigns or television debates. I thought about that photograph. I thought about what it meant for Chicanos in Colorado and across the Southwest to see a national Black leader show up in their spaces — not as a guest, but as an ally.

By the early 1980s, I was sitting in the Arapahoe County Democratic Central Committee as an observer, learning how power actually moves. The committee endorsed Jackson for president. That vote wasn’t naïve. They knew the odds. But they also knew what his candidacy represented.

Ambition without apology.

Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 campaigns did something profound for Latino communities. They built support in East Los Angeles and other heavily Latino areas, speaking directly about shared struggles against marginalization. He did not treat Latino neighborhoods as symbolic stops. He understood coalition as leverage.

He opposed the 1984 Simpson-Mazzoli immigration bill, which many in the Chicano community viewed as punitive. He pushed for greater funding for education and social services that affected both Black and Chicano communities. And he constantly urged Latinos to register to vote, calling the ballot the “crown jewel” of civil rights — the difference between potential power and actual power.

That language mattered.

The Black Civil Rights Movement had already secured sweeping federal victories — the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 reshaped American law and politics. Leaders like John Lewis, whom I later knew when he was in Congress, carried that moral authority into government.

The Chicano movement fought on different terrain. Chicanos battled for bilingual education, fair representation, farmworker protections, land rights, and cultural recognition. They struggled with internal fragmentation — ideological splits, personality clashes, and the constant pressure of federal surveillance programs that thrived on sowing distrust.

Chicanos lacked a singular federal target like Jim Crow. Their fight was often against invisibility itself.

Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition model widened the map. It showed that marginalized communities did not have to remain regional protest movements. Chicanos could think nationally. They could organize beyond identity silos. They could compete.

Yes, he stumbled. His “Hymietown” remark in 1984 was offensive and damaging, particularly to Jewish allies who had long stood with the civil rights movement. That wound was real. Movements are led by imperfect human beings.

But from a Chicano vantage point, Jackson’s legacy is larger than a single misstep.

He modeled coalition as a strategy.

He demonstrated that minority ambition at the highest levels of American politics was not arrogance — it was assertion.

Even after his presidential campaigns ended, he continued speaking against ethnic disparity and policies he believed demeaned communities of color, including opposition to the construction of a border wall that targeted Latino communities.

Today, Latino politicians hold office across the Southwest. They have seats at the table. Whether they still carry the ganas of earlier generations is a question history will answer. Institutions cool passion. Power demands compromise.

But that 1973 photograph reminds me of something essential.

Before representation became routine, solidarity was deliberate.

Before coalition became campaign language, it was risk.

Before Latino political presence was normalized, it was imagined.

Jesse Jackson helped expand that imagination.

And for those of who watched from Chicano spaces — and sometimes sat in party rooms daring to endorse him — that mattered.

It still does.